THE HISTORY OF ART:

A FRAMEWORK

"There’s a point at 7,000 RPMs where everything fades.

All that’s left, a body moving through space, and time.

At 7,000 RPM, that’s where you meet it. That’s where it waits for you."

In the 16th century, the Italian artist Giorgio Vasari created The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, a series of artist biographies primarily focused on the Florentine Renaissance. For Vasari, a narrative and biographic angle was the best approach to talk about art. As another example of past methods of organizing art history, most museums arranged artworks in chronological order. However, both the biographic and chronological approaches de-emphasize the formal qualities of artwork, as well as limit global and cross-cultural connections that could be discussed.

Today, it instead makes sense to categorize art into three categories that could describe all art: naturalism(optical realism), abstraction and synthetic representation. These terms provide a formal—not subjective or interpretative—framework with which to navigate art, across various contexts of time and place.

Naturalism

Naturalism defines paintings in which the mode of representation overlaps with the optical perception of reality. In other words, naturalistic paintings represent almost exactly what one would see if standing in front of those same objects in real life. Naturalism as a style of art originated in the early Renaissance and further developed according to both Northern and Italian Renaissance ideas.

Naturalistic works employ optical realism, or the illusion of three-dimensionality. In the Italian Renaissance, compositions emphasized a rational and even mathematic order. The images are stable and serene, rather than sensual or emotional. There are no harsh shadows. The space is simplified, often using architecture to create grids and contain the figures.

This style also introduced a new relationship between art and the viewer—the perspective viewpoint in these paintings is typically single point and central, therefore centering the viewer and seemingly presenting the painting to them. This corresponds to prevailing ideology of the time, with a shift towards human reason and knowledge. An organized, utopian idea of the world is presented.

Renaissance paintings also frequently depicted scenes from classical mythology and religion, which became a growing theme in Western art. Many Italian Renaissance painters were deeply inspired by the elegant, white marble sculptures of classical Greece. Classicism is specific philosophy, rooted in Ancient Greece and Rome, that underscores the importance of society and logic.

Synthetic representation

In synthetic representation, objects are summarized and reduced to their essential elements. This allows viewers to comprehend works quickly and more instinctively.

Cave paintings are not illusionistic, but they are clear representations of animals. They emphasize the outlines and the most recognizable features of each animal, a kind of visual shorthand. The intent of cave paintings remains unclear. Some historians believe they provide instructions on hunting, while others believe they are shamanistic drawings.

Idealization is a powerful tool of synthesis. The ancient Greeks believed in the importance of a healthy mind and healthy body. Sculptures of the time are consequently idealized. They are not accurate representations of real people, but rather conceptual representations of an ideal.

Similarly, Roman busts were invented to preserve power. These sculptures are flattering portraits of emperors and military leaders, highlighting their strength and vitality. (There is less emphasis on beauty than in Greek sculpture, so they appear more realistic.) The busts were also more portable than full-sized sculptures, so they could be traveled to different regions of the Roman empire and used as propaganda.

Medieval art also exemplifies synthetic representation, as opposed to naturalism. Most of the population in Europe was illiterate, and therefore images were used to share cultural narratives and religious stories. Here, synthesis is used as an educational tool. The message of the artwork is prioritized over its aesthetics. The images are simplified and structured hierarchically; larger figures are more important than smaller ones, for example, like Mary and the infant Jesus in the above painting.

In 17th century Europe, the Protestant church criticized the Catholic cult of images and believed that representation of religious figures was a form of idol worship. While artists in Catholic nations still enjoyed the patronage of the monarchy and the Church, artists in Protestant regions were instead supported by the growing middle class. Images made during the Northern Renaissance, the Dutch Golden Age and the Baroque period consequently focus on landscapes, still lifes and scenes of everyday life, rather than religious imagery.Make it stand out.

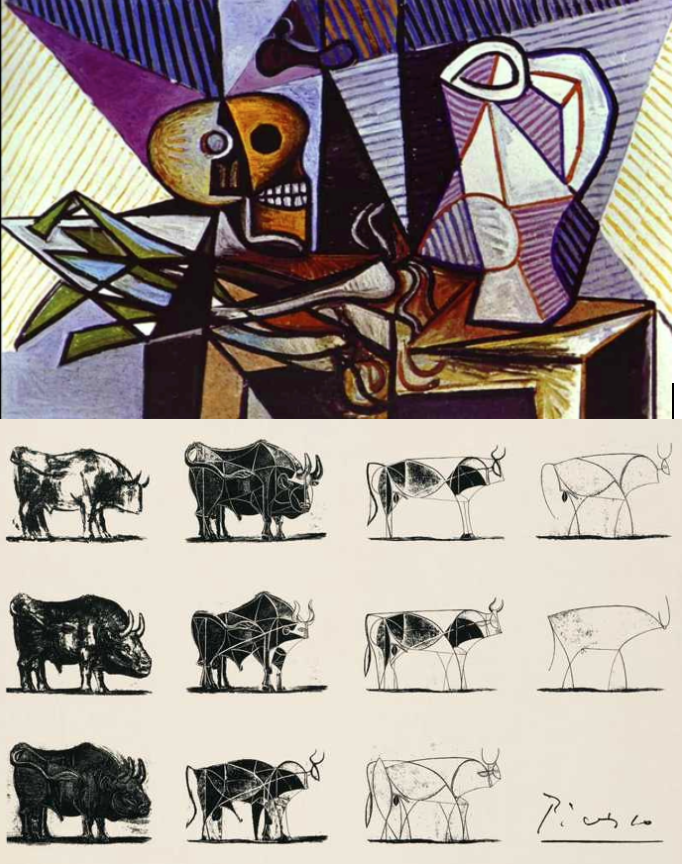

Typically, Dutch still lifes or “vanitas” paintings are layered with symbolism. They often allude to the transience of beauty and the inevitability of death—rotting fruit, withered flowers and timepieces or hourglasses act as “memento mori,” or reminders of mortality. Some paintings expressed pride in local Dutch products, while others boasted of wealth and international trading with foreign spices and exotic goods.

This painting may initially look like a naturalistic painting. However, it is not a depiction of an actual bouquet or even a realistically possible flower arrangement—it is an invented image with symbolic meaning. The vase contains multiple kinds of flowers, which each bloom in different seasons and some of which did not grow natively in the Netherlands. So in reality, these flowers could not possibly be seen at the same time. Notably, one of the flowers is a Semper Augustus tulip, the most expensive type of tulip, and therefore suggests wealth and extravagance.

Later, Romanticism emerged during the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, as artists sought reconciliation with nature. They rejected rationality and productivity, instead embracing humanity and its emotional complexity. Romantic artists prioritized the individual over society, assigning the individual their own critical authority.

Romantic artists frequently sought to represent the sublime. According to the theory developed by Edmund Burke in the 18th century, the sublime refers to greatness beyond measurement. Burke believed that sublimity and beauty are mutually exclusive; a beautiful image may be aesthetically pleasing, while a sublime image stirs a strong emotional reaction in the viewer. Romantic paintings explore nature as an experience of the sublime, often working at a grand scale to physically envelop the viewer and viscerally convey the feeling of smallness or inconsequentiality in the face of nature.

For example, the aim of the above 1817 painting by Friedrich is not to create an accurate historical account but rather to evoke a sense of loss and sadness. The artist intended to capture the emotions that he himself felt and allow the viewer to experience them too. How does he accomplish this? Certainly not through optical realism, which emphasizes the appearance—he does this using synthetic representation, emphasizing the experience.

The 1838 painting by JMW Turner is remarkable in the way the artist creates light through fluid and loose brushstrokes. He deftly communicates the brightness, drama and atmosphere of the landscape.

Rather than using central perspective, the sail ship and the tug boat are located on the left of the painting and so, to draw attention to the subjects, Turner conveniently places them in a blue triangle which contrasts with the warm colors of the setting sun and its reflection in the water. Perhaps the orange hues are too exaggerated to be realistic, but again, Turner and other Romantic painters are not concerned with optical realism but with evoking a particular atmosphere.

In the 20th century, particularly during the Cold War, the Soviet Union commissioned many public works of art, particularly enormous sculptures of workers. They are powerful pieces of propaganda, evoking a sense of national pride and promoting the worker as the hero of communism. In the work on the left above, for example, a male worker holds up a hammer while a female farmer holds up a sickle.

(In response, the CIA created Operation Mockingbird in the United States, an effort to manipulate news media for propaganda purposes. Abstract Expressionism represented distinctly American values—freedom, individuality and experimentation. It was leveraged as evidence of the intellectual freedom and cultural prowess of the United States, in contrast to the restrictive aesthetics of Russian art that celebrated communist ideologies. Artists like Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko never received money from CIA but some of their travel expenses were financed.)

Abstraction

Abstract art does not aim to represent an accurate depiction of reality but instead employs shapes, colors, forms and gestures to achieve its intended effect. Abstract art may still reference reality; it is specifically non-representational art that does not intend to reference visual reality to any extent.

Importantly, abstraction is not the exclusive invention of the Western world. In fact, Western abstract artists were initially inspired by ancient Iberian and African sculpture. (In modern Western art, this style of borrowing from non-Western traditions came to be known as “primitivism.”)

With the rise of photography, painting and sculpture become redundant as means of realistically representing the world. What is the point of painting, if accurately representing objects is no longer its main objective? The avant-garde—meaning unorthodox and experimental ideas in the visual, literary or musical arts, as well as the people who champion them—answered this call. Illusionistic artwork, whether naturalistic or synthetic forms of representation, thus gave way to abstraction in the early 20th century.

One early abstract movement that revolutionized European painting and sculpture was Cubism. Up until this point, most art reflected a recognizable vision of reality. Cubism instead offered images in fragments, suggesting a new way to organize and understand images. Cubism also created an interest in materiality, particularly through collage. Artists began to push painting as far as possible from the flatness and refinement of photographs, which already fulfilled the function of accurately recording what people see.

Artists in the early and mid-20th century were keenly interested in the issue of representation. Painting was ultimately pushed to “degree zero,” the point at which the image is reduced until the composition is absolutely based on geometrical balance and harmony.

A pioneer of abstract art, Kandinsky was interested in synesthesia and creating a multifaceted experience of visual art. He wanted to guide the viewer to a spiritual experience, rather than relate to something in reality. Over time, his painting evolved from abstract to fully non-representational, developing a style characterized by explosions of form and color.

In Russia before the revolution, Kazimir Malevich developed Suprematism, a style of art centered on basic geometric forms such as circles, rectangles and lines, painted in a limited color palette. Suprematism was associated with spiritual purity, and it advocated for “the supremacy of pure artistic feeling” rather than the visual depiction of objects.

Piet Mondrian was an important leader in the development of modern abstract art, known for his involvement in the Dutch art movement called De Stijl. In the pursuit of “universal harmony,” which had a strong spiritual connotation, he reduced his visual language to the bare essentials of form and color. Mondrian typically relied on black, white and primary colors along with hard-edged geometric shapes. De Stijl ultimately influenced architecture, design, fashion and the German art school Bauhaus.

These movements (and later ones like Abstract Expressionism) were not attempting to capture the world. Instead, they intended to capture the inner world. They were also influenced by the cult of theosophy, or the belief that knowledge of God can be achieved through spiritual ecstasy or intuition. These artists wanted the viewer to stay in front of the artwork and meditate—a spiritual visual experience was the goal. While these artworks may appear cold and detached now, in actuality they are the opposite of the Bauhaus movement’s emphasis on pragmatism and simplicity.

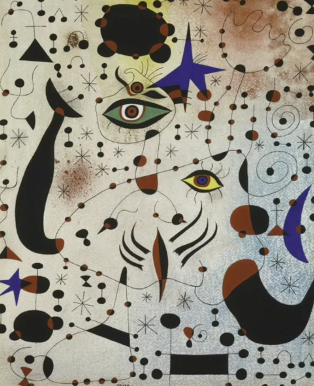

A fellow Surrealist, albeit with his own signature take on this style, Joan Miró was inspired by Freudian’s theory of free association. To access the unconscious mind, he created automatic paintings featuring very simplified and even childlike shapes. His paintings do not represent objects but rather interior mental states.

Miró’s painting above blends together telescopic vision and microscopic vision. Eyes and stars are clearly depicted, but also vague geometric shapes and curving lines. These marks are suggestive of a bodily form but not representative.

Miró frequently expressed distaste for traditional painting methods, which he saw as a way of supporting bourgeois society and its values, and instead he advocated for the “assassination of painting.”

Cy Twombly reinvented painting. The righthand painting above aims to capture the essence of Bacchanalia, the Roman god Bacchus’s infamous nighttime parties known for orgies, wine and the return to animality. Twombly asks, how do you represent an experience of that intensity? Typically, Renaissance art depicted the aftermath of the debauchery, but instead Twombly captures the intensity of the moment. His work is an abstract gesture towards the frenzy and passion of the Bacchanalia.

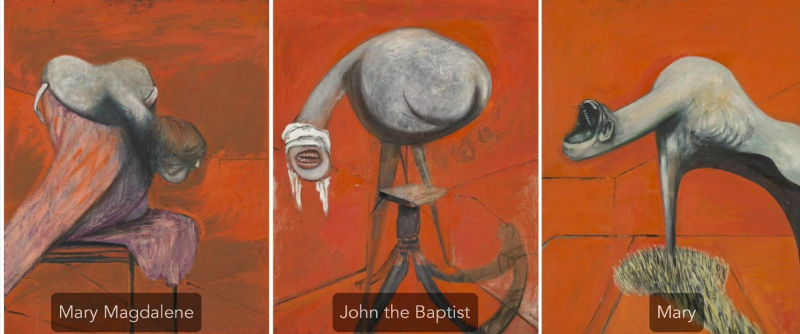

These studies by Francis Bacon distort each of the animal-like figures to demonstrate the physical depth and impact of deep emotional pain. The title suggests that the three figures correspond to traditional religious paintings of the crucifixion of Jesus, but they are not based on any real creatures. Painted in 1945, this work also suggests the horror and anguish felt during the conclusion of World War II.